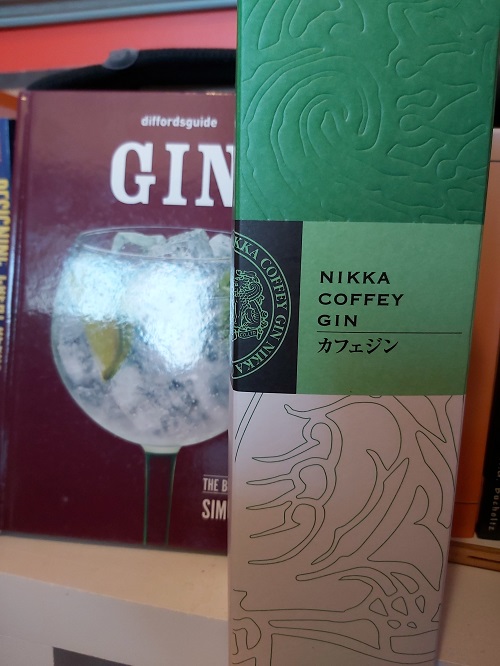

Do you fancy bold citrus notes in your Gin? If you do, keep your eyes open for this amazing Gin its iconic green and white box. Nikka distilling has a solid reputation for Japanese whisky, so when I first saw this Gin product, I just had to have it. I reasoned that if Nikka put as much attention into making this Gin as they do into making their Whisky, it would be top shelf good. Don’t fuss over the name Coffey. That is the type of still Nikka uses to create its base alcohol for making the Gin. I have seen Nikka Gin in BC and Alberta to date. Prices range from $68 to about $78. I drink this Gin with just a wee splash of water to open it up. The distinct citrus comes from yuzu, kabosu and amanatsu Japanese citrus fruits. The bit of spice on the finish comes from sansho pepper. Treat yourself right. Get a bottle of Nikka Gin. Enjoy!

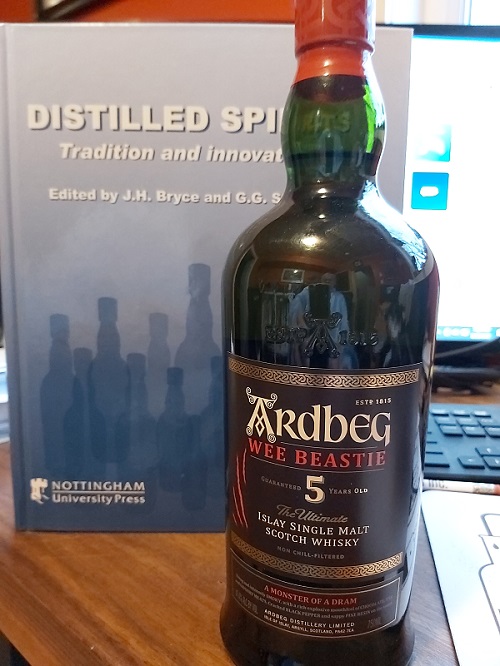

Wee Beastie

Sit up straight in your chair and brace yourself. When the makers of this Scotch named it the Wee Beastie, they knew what they were doing. At only 5 years old, this is a hulking, brute of a dram that can reduce you to a simpering, sobbing mess, curled up in the fetal position on the floor if you do not afford it some respect. But, add several drops of water and the beastie retreats to leave you with wonderful campfire smoke combined with elegant sweetness and a touch of citrus on the finish. This Scotch will be given a special place on my shelf…. I am beyond impressed!

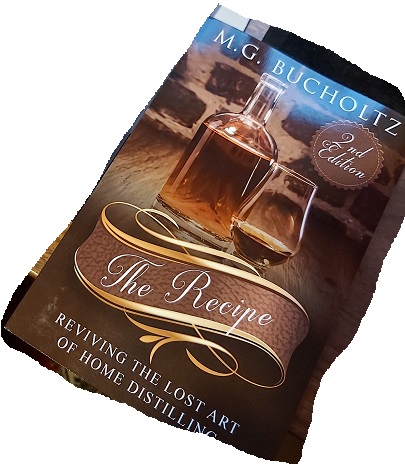

Hot Off the Press (Again!)

With distilling workshops not possible over the past several months due to Covid restrictions in Canada, I took the time to update my books.

The 2nd edition of The Recipe is now available on Amazon in paperback format and on Kindle & Kobo in eBook format.

If you are wondering about the title of this book, think waaaay back in time to a TV show called The Waltons. Two characters that made occasional appearances were a pair of elderly spinsters. Their father had been a Judge before he died. But he apparently had also been a home distiller. In episodes where these ladies appeared, they would always display hospitality to visitors by offering a drink of the “Recipe”. One of them would then toddle off to the basement and return with a mason jar full of clear liquid.

The 1st edition of The Recipe was released in 2016 and shortly thereafter was banned for sale due to its provocative title. But that was then. Society has evolved over the past 5 years to the point where “weed” is now sold at retail shops and individual home-owners can grow up to 4 plants in many locations. Likewise, home distilling no longer carries the stigma that it did 5 years back.

This book contains an easy to read presentation of the science and the equipment you will need to make your own product. Just bear in mind, that whatever you make should be used for personal consumption at your house. Do not be giving it away or selling it.

I hope that as vaccines roll out over the next month or two, Covid will recede back into its corner. I hope to be offering workshops in Calgary again soon. If you want to become a serious home distiller, give some thought to taking one of my workshops….

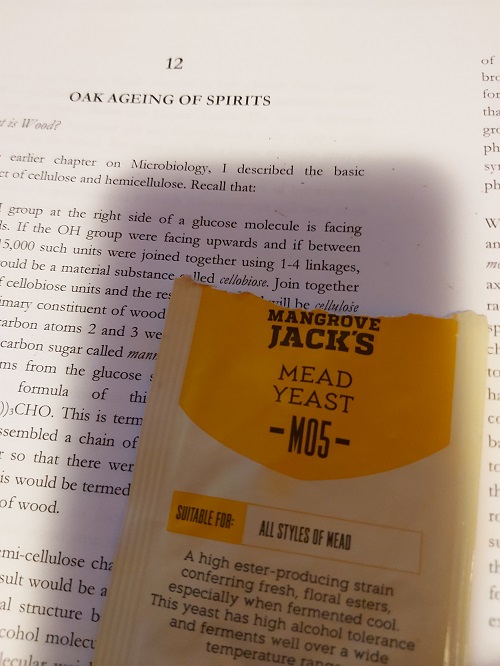

Yeast – The Importance of Floculation

Recently I took a break from updating my Field to Flask book. I used this brief break to make a batch of raspberry mead. I used 1/3 tap water from Mossbank, SK where I reside and 2/3 RO water. I added some additional CaCl2 as well. By my calculations I had close to 100 ppm Calcium in my process water. I decided to use a yeast I had never heard of before called Mangrove Jack’s Mead Yeast. It is made in new Zealand from what the package says. The best before date on the packet is Dec 2021, the attenuation is listed as high and the floculation as high. My OG was 1.080 which according to the yeast packet is suitable for the yeast which is alcohol tolerant to 18%. The ferment was slow, taking 15 days to ferment. I have since moved the mead into a keg and it is carbonating now. I am disappointed with the floculation of the yeast. For sure, it does not rate as high my by observations. According to the yeast book of knowledge by Boulton & Quain, yeast will floculate and drop to the bottom of the fermenter because surface proteins on the yeast cell will bind to carbohydrate receptors on neighboring cells. There are a series of genes that have been identified ( the FLO genes) that also play a role in floculation characteristics. To date, I have brewed many batches of beer with combinations of tap water and RO water. No problems with floculation on the beers, so I know it is not the water chemistry at fault. I am sorry to say that I think Mangrove Jack’s mead yeast is at fault. I have several more batches of mead to make in the coming months. I will NOT be using Mangrove Jack yeast for any more batches. If you are reading this post and have used Mangrove Jack’s yeast, I would like to hear from you about your experiences (good or bad). Meantime, I will have to navigate my way through one batch of hazy mead. Won’t kill me, but it is not something I want to serve up to a guest.

The Gin Act of 1736

Hey Gin drinkers! Was doing a bit of late night history reading over a few drams last night.

Did you know….. on Feb 20, 1736 a petition was presented to the British House of Commons asking for regulation on Gin. The petition alleged “that the drinking of Gin had excessively increased amongst people of inferior rank”. This excessive consumption had “destroyed thousands and rendered great numbers of others unfit for labour, had debauched their morals and had driven them into every vice”.

What came of all this was the Gin Act of 1736 which passed on Sept 29, 1736. The Act imposed a tax of 20 shillings per gallon on Gin plus a 50 Pound annual license fee on retail sellers of Gin.

BUT, the Act was evaded. People pretending to the “chemists” set up shop selling Gin as baby’s colick water. Gin also started to be sold under disguised names such as Tom Row, Make Shift and Ladies Delight.

By 1743, Gin intake had actually increased. To counter this, Gov’t encouraged the drinking of Rum from the Colonies, provided that it was sold to the retail consumer at 1 part Rum and 2 parts water. This came to be known as “2-water grog”. But that’s a story for another time…

source: The Historians History of the Word, vol 20, published 1904.

Face the Monster

Put down that smooth mellow Scotch that hails from Speyside or the Highlands.

Take an adventure to Islay, the home of all things peated.

The blenders at Compass Box have sourced several single malts from Caol Isla and one expression from Laphroaig. The net result is what is termed a blended malt. At school during my M.Sc. studies I was led to believe that blended malts were the exception with blended Scotch whisky being more common. The distinction is, a blended Scotch comprises a base distillate to which malt whisky has been added. A blended malt is a blend of just malt whiskies with no base distillate to take away from body, texture and mouthfeel.

Powerful, assertive, in-your-face, are descriptors that apply to the Peat Monster. When I pour myself a dram and settle into my leather armchair, my wife says she cannot handle the peat aromas coming from my glass and runs screaming from the room. Like I said….this stuff is powerful.

I have done the usual suspects from Islay, at least to the extent that they are available to me in Canada. I have sampled Lagavulin, Laphroaig, Bowmore and a couple variants of Ardbeg. All good to be sure. But nothing impresses me like the Peat Monster.

To John Glaser and his team at Compass Box, I say well done gentlemen! Keep the creative expressions coming. And keep sending product to Canada.

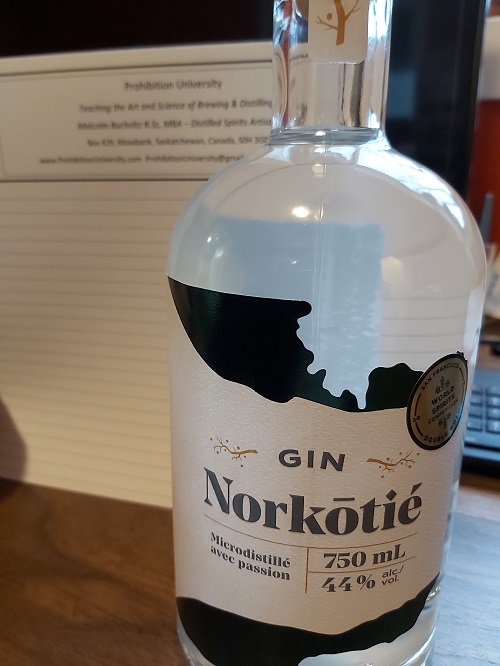

Gin Norkotie

I recently received a bottle of this fine Gin from Distillerie Vent du Nord in Baie Comeau, Quebec. This creator of this fine nectar took my Workshop in 2017.

I drink all my Gins with just a splash of water to open up the flavors. In the case of this Gin, I get a wonderful hit of sweet earthiness likely from Angelica Root and Licorice Root. There is also some very pleasing citrus woven into this Gin. The finish is smooth with just a hint of spice.

I could drink this Gin every day, all day. I am giving it a rating of 96/100 on the Prohibition University Gin Scale.

If you are in Quebec, you will find this Gin at any SAQ store. Outside of the Province, you will have to ask your local private liquor store to contact Distillerie Vent du Nord and arrange for a shipment. This will trigger some provincial liquor taxes based on the wholesale selling price.

Admiral Rodney

I am always on the look-out for unique Rum. On a recent trip to Calgary I went to one of my favorite liquor stores – Craft Cellars on 32nd Ave just off Deerfoot. There I found a Rum from the island of St. Lucia called Admiral Rodney.

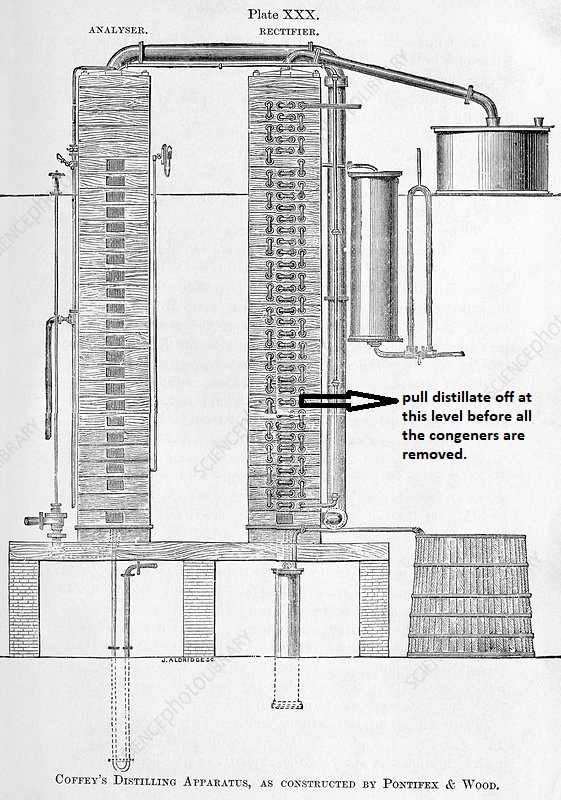

What intrigued me was the description of the distillation method on the packaging. The distillery uses a Coffey Still, the basic design of which extends back to Anneas Coffey in the late 1800s. Coffey Stills are used at a number of locations around the world today and owing to their 2-column design the distillate coming off the still will be in the range of 95% abv.

But, in St. Lucia, the distillery pulls the distillate off at a point lower down on the 2nd column which means more of the higher molecular weight alcohols are retained in the distillate rather than getting stripped away by being allowed to travel higher up the column.

In my Workshops I talk about the Coffey Still and the principles behind the use of columns versus pot stills. Anyone who has taken my Workshops will tell you I am a huge proponent of leaving the higher molecular weight alcohols in the final distillate. If you don’t, you are creating a distillate stream comprised of ethanol and de facto almost a Vodka. The consumer will then mix the spirit drink with cola or ginger ale to give it some semblance of flavor. What a waste!

Admiral Rodney Rum is a blend of Coffey Still-produced Rums that are between 5 and 9 years old. All I add to my dram of Rum is a dash of water. Admiral Rodney Rum is a divine pleasure to sip.

Author Dave Broom in his book Rum: The Manual claims that Admiral Rodney Rum is good with a wee dash of coconut water. I have not tried this technique, but will aim to do so.

As 2021 dawns, treat yourself right. Invite the Admiral into your house…..

What’s In Your Beer?

Arsenic is on my mind.

Late one evening just recently, I read a study where the authors used Indian black rice and Italian white rice to make a lager style beer (1). All good, right? After all we know that rice is a key ingredient in many commercial beers.

Then the researchers dropped a bombshell. I am still not certain why they dropped this bombshell. Perhaps to make a social statement? They could have simply concluded their research with a favorable recommendation for using black rice as a raw material for making beer.

The bombshell – rice is notorious for its ability to uptake arsenic from the soil. The Indian Rice gave beer with 15 ppm arsenic. The Italian rice gave beer with 28 ppm arsenic.

This revelation led me to another academic paper (2) that studied 19 different beers from around the globe. The average arsenic level in this sampling of beers was 11 ppm. It turns out that barley also can uptake arsenic from the soil. Italian ales and lagers made with rice and/or barley had about 15 ppm arsenic (not so good!). German Hefe Weizens had 2-6 ppm arsenic (excellent!). Irish Stout had 2.7 ppm arsenic (again, excellent!). Japanese lager had 10 ppm arsenic (in line with the average). Scottish strong lager had 20 ppm arsenic (not good!).

Before you reach for your next beer, stop and consider where it is from. Where was the barley grown? If the beer is made with rice, where is the rice from? Hint – a lot of barley in the USA comes from Idaho and Colorado, both of which have areas with higher arsenic levels. Thankfully, American rice is low in arsenic. Without naming specific beers, I think we all know what beers are brewed in Colorado. I would really like to see some analytical data for these commercial beers to satisfy myself that they have low arsenic. But I doubt I will see this data. Funny thing about toxins in food and drink. The data is often carefully managed so as to avoid public outcry.

One on-line study (3) I found claimed that certain soils in the grain growing region of northern Alberta have high arsenic levels. I have not been able to find Saskatchewan geochemistry soil data. I would like to, as we do have a malting plant in Biggar, SK.

And, now for the kicker. Glyphosate type agrochemicals have varying levels of arsenic (4), ranging from 2 to 31 ppm as cited in a 2015 study. A 2014 study by the same lead author went so far as to name some agrochemical names: Propanil, MCPA, Mancozeb, Chlorpyrifos, Carbofuran, Diazinon, Profenofos, Carbosulfan, Pretilachlor + Pyribenzoxim (5). How a glyphosate product works is, it disrupts a key metabolic pathway responsible for amino acid synthesis. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins needed for plant structural growth. Weeds are plants, ergo a farm operator applying glyphosate type products at the appropriate time can inhibit weed growth (6). Moreover, glyphosate type products readily chelate (bind) with soil elements such as arsenic and remain in the soil. A growing plant such as rice or barley will then uptake the chelated arsenic molecules (7). I think we all know the name of one glyphosate type product that is common to North American agriculture. Hello RoundUp! To be fair, I have not seen a chemical analysis of RoundUp and so cannot say whether it has high or low arsenic content. A reasonable question to ask, however, is “What is the average barley grower putting on his fields?”. If this talk of arsenic in agrochemical doesn’t make you stand up and cheer for organic farming, nothing will.

As for me and my long-term health, I am going to stick to German Hefe Weizens and Irish Stouts when I next stop at the SLGA Liquor store in Assiniboia, SK.

Here is the big question and one that I am sure will not be welcome in beer brewing circles: does anyone out there have arsenic geochemical soil data for Saskatchewan?

If you do, please share it.

Here is another big unwelcome question: does anyone have chemical composition analytical data on malt barley from Canada Malting in Calgary or from Prairie Malt in Biggar, SK. ?

If you do, please share it.

This entire accidental late-night discovery of this sensitive subject has really got me thinking. We have seen how Monsanto has quietly slipped away and merged with Bayer. Lawsuits in the billions of dollars have dogged (and continue to dog) both Monsanto and the now merged Monsanto/Bayer entity. Courts of law have decided that glyphosate chemicals are bad.

I am not trying to hurt beer brewers or malting companies. But arsenic and other heavy metals are cumulative in the human system. If you are a beer drinker, as I am- in a big way, don’t you owe it to yourself and to your family to figure out what (if any) heavy metals such as arsenic are in the beer you drink? If a brewer is using a certain type of malt that may have above-average arsenic levels, does that brewer not have a moral obligation to explore other malt brands from different geographic areas that might have lower heavy metal assays? Do malting companies not have a moral obligation to source barley from farm operators using safer farming practices?

I will leave it at that for now. I think I have stirred up more than enough controversy.

- Kamaljit, M, et al (2020) Indian Black Rice: A Brewing Raw Material with Novel Functionality. J. Inst. Brewing, (126), p 35-45.

- Donadini, G., Spalla, S., and Beone, G. M. (2008) Arsenic, cadmium and lead in beers from the Italian market. J. Inst. Brew. (114), 283–88.

- Dudas, MJ (1987) Accumulation of Native Arsenic In Acid Sulphate Soils in Alberta. Can. J. Soil Sci. 67:317-331.

- Jayasumana et al (2015) Phosphate fertilizer is a main source of arsenic in areas affected with chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Sri Lanka. Springer Plus. 4:90, pp: 2-8.

- Jayasumana et al (2014) Glyphosate, Hard Water and Nephrotoxic Metals: Are They the Culprits Behind the Epidemic of Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Etiology in Sri Lanka? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health (11), pp:2125-2147.

- Malik, J.; Barry, G.; Kishore, G. (1989) The herbicide glyphosate. BioFactors. (2), pp:17–25.

- Caetano, M. et al (2012) Understanding the inactivation process of organophosphorus herbicides: A dft study of glyphosate metallic complexes with Zn2+,Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+, Co3+, Fe3+, Cr3+, and Al3+. Int. J. Quantum. Chem. (112), pp:2752–2762.

Getting the Most out of a Gin Run

In our Gin Master classes, there are always plenty of questions about Gin distillation parameters. My Microbiology Prof from Heriot Watt University and one of her pH.D. candidates just released a paper that confirms a lot of my practical hands-on observations across the 100+ Gin creations I have done either myself or in a Gin Master class.

I will skip the heavy academic content and summarize the findings in a simple way:

The more Juniper you add to your recipe formulation, the more intense the Juniper notes will be in the final Gin. This was confirmed in their study using sensory panels of 20 persons. For my small scale 3-Liter recipes I usually add 60 grams per liter of 96% ethanol. I have in past added more and yes, I get a more intense Gin.

Doing the distillation run low and slow will extract more Juniper notes into the final Gin. This seems intuitive, but now there is scientific data to support the matter. Making Gin is not a race. Take it easy, and slow down. A slower run will give the ethanol more time to extract the oils from the Juniper.

Diluting the ethanol charge in your still to 45% will give more Juniper note extraction ( versus a 60% abv dilution). I have always viewed this as intuitive. A more dilute charge in the still takes longer to heat up. Remember q=(m)(Cp)(deltaT). All that extra water in the still takes energy and time to heat to the point where the ethanol vaporizes. But, now this study proves out this notion. In the Gin Master classes I typically dilute the ethanol to 50%, but I may start using 45% to see what happens. For a home connoisseur in possession of a small copper A’Lambic still, store-bought Vodka at 40% would even suffice just fine in the still.

This is the kind of academic research that I really appreciate because it ties so forcefully to the practical realities of distilling. I look forward to hopefully seeing more content of this nature from Heriot Watt…