My sage advice to craft distillers is – know the market. I am seeing too much evidence of late that craft distillers fancy themselves to be part of the “high end” of the market spectrum. The concept of “high end” only exists because of marketing, which requires deep pockets. I have yet to meet a craft distiller whose pockets reach down to the ankles.

First off, why do humans drink a liquid that alters mood and physical motor skills? The answer is the alcohol “drug” helps us deal with the pressures of daily survival. It eases the stress, it helps us relax. Alcohol in the short term increases our energy levels. Millions of years ago, being able to deal with the stress of survival was important to our primate ancestors. Increased energy helped primates find food quicker than competitors. Geneticists claim that a single point DNA mutation millions of years ago allowed some of our primate ancestors to metabolize alcohol. This ability is with us today in the form of the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme in our livers. Over time, the primate species who did not acquire this DNA mutation died off because of their inability to digest alcohol. The surviving primates were homo sapiens, from whence we derive.

The key take-away is – we do not drink for show, for glamor or for glitz. People of all socioeconomic means drink beverage alcohol. Drinking is embedded in our DNA structure. It is part of a our basal behavior. Drinking is not limited by social status or income.

Have you noticed that manufacturers of goods and providers of services have a predisposition to segregate the marketplace into high end, middle and low end categories? Take a look around. Have you driven past a BMW dealership lately? Have you driven past a Chev or Ford dealer? Have you driven past a corner car lot that is selling well-worn, used vehicles? Pick any consumer product and you will see this same upper, middle and lower strata model being applied.

Many of the consumer products we buy are extensions of our personalities. They make a statement. They speak to self actualization. American psychologist Abraham Maslow summed this observation up in his Maslow Hierarchy of Needs, which resembles a triangle. At the bottom of his triangle, we all need food, clothing and shelter. As we move up the triangle we start to want items that demonstrate to the world that we have attained success.

This upward progression in the triangle is what has prompted makers of goods and providers of services to advance the concept of high end, middle strata and low end. Don’t buy that Chevy car. Buy a BMW because it makes a statement about who you are. Don’t buy a cheap laptop. Buy one with more bells and whistles on it, Maybe one that has a piece of fruit as its corporate logo. Don’t buy your next set of eyeglass frames at a department store. Get fancy designer frames instead.

To a craft distiller placing products in the marketplace, it seems only natural to apply this stratification model. It seems only natural that craft distillers would want to target the upper part of the market spectrum. Craft distillers put a lot of work and effort into their products. They grind their own grain and spend hours on a hard concrete floor watching liquid drip from a still. Surely this deserves recognition and monetary reward? I have yet to meet a craft distiller who regards his or her products as only being suitable for the lower part of the consumer spectrum.

But, the reality is, when it comes to alcoholic beverages, the market stratification effort runs into trouble. Alcoholic beverage is difficult to fit into the Maslow Hierarchy. We do not suddenly take up drinking alcohol as we ascend through a particular level of the Maslow Hierarchy. Alcohol consumption is tied to our very basic needs, lower in the triangle. People consume alcohol today for the same basic reasons that existed back in the days of tree-swinging primates: to energize, to relax, and to cope. This list can be expanded to the modern era to include drinking to reward and drinking to commiserate.

Despite this reasoning, alcohol makers like to speak of “premiumization” as they try to apply the market stratification model. Certain brand names in the portfolios of big alcohol makers are deemed to be premium brands. The premium issue is complicated by the fact that distilled alcohol, even at 40% abv, is a bit tough to navigate for most people. So, they end up diluting their alcohol with water, soda, juice and so on. Or, they fabricate the alcohol into cocktail drinks. If the distilled alcohol did have a unique taste profile, mixing it will quickly erase that profile. So, why buy premium then?

To counter this mixing behavior, the big alcohol makers have resorted to spending huge money on advertising to create and reinforce the idea that certain brands are more upscale and premium than others. In my many Workshops over the past 6 years, I have done blind taste tests on vodka, where I have diluted the vodkas to 30% to alleviate taste bud fatigue. You would be inclined to think that Grey Goose would have come out on top of these taste tests. But, shockingly, it did not. Vodka is nothing more than ethanol created using a continuously-run distilling process such that the distillate comes off the still at 96% abv. The ethanol is then diluted to 40% abv with water and bottled. What makes Grey Goose high end is its advertising and imagery. Grey Goose does not advertise in 4×4 Off-Roading type magazines, nor does it advertise in blue-collar Hunting and Fishing magazines. Rather, Grey Goose advertises in Conde Nast Traveler and other upscale such mags. Grey Goose will advertise in bus shelters in downtown Vancouver where people of means and disposable income can be found. Grey Goose uses a frosted bottle and screened labels to differentiate itself from vodka in plain glass bottles with paper labels. Grey Goose then assigns a higher price point to itself to fully drive home the fact that it is premium. The cost of creating this high-end image is certainly not cheap. But, to parent company Bacardi, who makes 400 million bottles of alcohol each year, the Grey Goose expenses can be offset across the entire Bacardi family of brands.

I have seen the same model applied to whisky as well. Macallan Scotch is good and I enjoy it. I also enjoy Aberlour Scotch. These two distilleries are located not 3 miles apart, on opposite sides of the River Spey near Craigellachie. The Aberlour visit is simple and straightforward. Mind the stairs and don’t trip on that water hose snaking across the floor. The Macallan visit is akin to a Disney experience. The price tag for their visitor center was a staggering 500 million Pounds. One is left with the distinct conclusion that Macallan is a high end brand. Its all in the imagery. It is all in the differentiation from the brand made 3 miles up the river. It is all about the money.

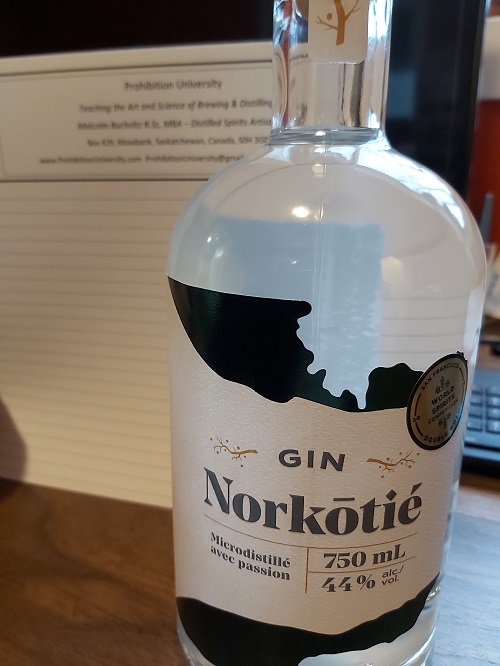

I am seeing overwhelming evidence of struggle and anguish in the craft distilling segment of the market. Craft distillers seem prone to assigning a high price point to their products with the reasoning that craft alcohol automatically has a place in the upper end of the market strata. Craft distillers are quick to emphasize that their products are grain to glass and therefore deserve a higher price point. I continue to shake my head in disbelief at this logic. The ethanol factory in France that makes the distillate for Grey Goose grinds its own grain, mashes it, ferments it, and distills it. Aberlour Distillery along the River Spey does likewise. Therefore, these brand names are also grain to glass. Perhaps if craft distillers were to advertise in select venues and through carefully chosen magazines, their argument would be better accepted. But – herein is the problem. Craft distillers do not have the money to advertise. In the world of whisky, there are some brand names that have released well-aged expressions of between 25 and 30 years old. I will agree all day long that these products are deserving of a place in the upper strata layer. Maybe one day when a craft distiller is sitting on an inventory of 20 year old product, the argument of high end can be made. But, not here. Not now.

Attempts to advance the grain to glass argument are further being hampered by technology. Take the case of the ethanol factory in Unity, Saskatchewan. It generates tens of thousands of liters of ethanol each week, most of it destined for gasoline blending. But, more and more, this distillate is finding its way into craft distilling circles. That craft distilled vodka you bought last week, could well be nothing more than ethanol from Unity, SK blended with water and placed in a decent-looking bottle. As makers of whisky and rum and tequila distillates embrace technology and strive for greater efficiency and greater output, the world finds itself with a surplus of alcohol. Hollywood movie stars have been alerted to this. A well-known actor (let’s call him George), with a few phone calls, can soon have his own (unaged) tequila-blanco brand made for him. Because he is so well known, and because he has money to promote his brand, it very quickly becomes associated with the “high end” market strata and retails for $74. The same distillery that made the distillate has also made distillate for cheaper tequila brands. The local craft distiller with no money for marketing is being shoved aside in his efforts to target the “high end” with a high priced product. The cry of “grain to glass” is becoming a muffled voice in the wilderness.

What has prompted me to write this pithy post, is the fact that craft distillers need to collectively wake up and assess reality. To position an alcoholic beverage in the upper part of the market strata requires a famous name, or money or both. To hold a product aloft in the upper strata will also require repeated infusions of marketing and advertising dollars. An upper strata, “high end”, product is only upper end because stardom, advertising, money, and imagery say it is.

Craft distillers need to get their prices down in alignment to what the big commercial players charge. There is no shame in targeting the other parts of the market strata. If a craft distiller is unwilling to lower prices, the craft road may soon get a lot bumpier for that operator.

For craft distillers just about to start their journey, my advice is to avoid the temptation to reach for the upper strata. Leave the upper strata to the movie stars and to the big players who have the big marketing budgets. Focus instead on creating products for the average person that are unique, mixable and drinkable.

The question then arises, should a person even bother making alcohol? In my experiences, craft distillers seem to be getting into the business for the ego thrill of making liquid dribble off a still. The hard reality is, the world is swimming in alcohol. Why make more of the stuff? Think about what could be accomplished by buying distillate from the big players. What could be blended, created, and concocted from that purchased distillate? Think about approaching an existing craft distiller and having product made on a fee for service basis.

As I explained to a start-up craft distiller recently, the craft “thing” was an economic bubble fueled by low interest rates and cheap borrowing costs. If I plot the monthly Workshop attendance numbers going back to 2014, the shape of teh curve is a bubble. Far too many people chased the bubble because they wanted to “make booze”. These people gave little or no thought to their target market and to brand image. They overspent and under-planned. They have failed to let go of the “grain to glass” notion. They have failed to let go of the idea their products deserve to be regarded as “high end”. They refuse to budge off the position that their products are worth $50-$60 per bottle.

I fear a wash-out is nigh for craft distillers. I am aware of several craft distilleries in British Columbia that have shuttered their doors in the past 6 months. I am aware of several start-up stories in other locales that can’t seem to find investment dollars to get their projects moving. I am aware of many small distillers that remain open, but the untold secret is that there is no money being made. Perhaps the term “zombie distillery” applies?

The consumer today drinks because that urge is encoded in our DNA. We drink to relax, to reward, to commiserate. Most people mix their alcohol to make it more palatable and more enjoyable. People want value for money. To some people, this means they seek out a premium brand expression. They do not know (don’t care?) that the premium brand is all about marketing and imagery. But, to the vast majority of people, value for money means something priced affordably that mixes well, and tastes good. As we move ever closer to a post-Covid world, craft distillers would do well to re-think their entire strategy. Leave the “high end” reasoning out of the equation. Focus on the average person and their beverage alcohol needs and wants. Strive to know the market.